A

R

T

I

C

L

E

S |

DARK

AUTUMN

THE 1916 GERMAN ZEPPELIN OFFENSIVE

On the night of October 1, 1916, the German Navy

Zeppelin L-21 was pushing her way through the high, thin air over Central

England near Norfolk. As the airship cleared a bank of clouds, her commander,

Captain Kurt Frankenberg, saw another zeppelin held in the bright glare of the

London searchlights 70 miles to the south. Strands of clouds drifted by

obscuring his view, and then with wondrous clarity he again saw the other

airship. She was in flames, glowing brightly in the evening sky and falling

quickly to the earth. L-21's captain and the few other crew members who saw

this dreadful sign were sure what they had witnessed. Another German airship

was out there this night, and it had just plummeted to the ground in fiery

ruin. They did not know it at the time but the blazing ship they had seen was

the German Navy Zeppelin L-31, commanded by airship ace Heinrich Mathy. His

death and the loss of his crew had far-reaching repercussions for the German

airship service.

"...you know that I'm no coward. Out in eastern

Asia we made many hair-raising voyages through typhoons. But I dream constantly

of falling zeppelins. There is something in me that I can't describe. It's as

if I saw a strange darkness before me, into which I must go."

Chief

Machinist Mate, German Navy Airship L-31

Introduction

At the start of World War One,

lighter-than-air technology was older than other aviation technologies of the

time and it showed much promise. The airships built by the Zeppelin Company in

Germany were gigantic machines by the standards of the day, and they were seen

as tangible fruits of the inevitable march of progress. An airship had graceful

lines, enormous size, and a characteristic sound; the drone of their great

multiple propellers beating the air. People seeing them were caught in a spell,

so impressive was the very sight of a zeppelin. The heavier-than-air aircraft

of the day were still rather flimsy machines, barely strong enough to carry one

or two people. It is no surprise then, that these lighter-than-air vessels

capable of lifting several tons were seen as the wave of the future for

aviation.

As the war progressed, the German navy and army each built

their own mutually exclusive airship fleets. The navy zeppelins however, were

usually of aluminum Zeppelin Company manufacture, whereas the Army often

used the wooden Shutte-Lanz or "SL" ships rejected by the Navy due to

their excessive weight. Both services began conducting bombing missions over

England, believing that aerial bombing would ultimately destroy that country's

industrial base. This overconfidence in the effectiveness of

turn-of-the-century high explosives paralleled similar beliefs in most military

circles at the time. It all combined into a powerful sensation that the awe

inspiring airships could never fail in whatever task they chose. For the first

year, it seemed they might be right. German airships ranged over England

impeded only by the weather. Flying heavier-than-air biplanes at night was a

still a very dangerous practice and the few planes able to find the airships

could do little more than put a few small holes in them.

By 1916,

there were two generations of German airships employed in combat. The L-13

through L-24 were older ships, which made up the majority of any attack force.

The newest ships were the L-30's, of which five had been built; the L-30, L-31,

L-32, L-33 and L-34. High hopes were pinned on these latest vessels. They were

far larger than the previous generation of zeppelin, with a hydrogen capacity

of 1,589,000 cubic feet, which gave them a much greater bomb payload. They were

however, only marginally faster and could climb no higher than their

predecessors, something not considered necessary at the time. No attempt was

made to anticipate the British reaction to being bombed with impunity. Since

all past methods of destroying zeppelins involved shooting them full of holes,

increased lifting capacity was considered to be an adequate solution. It would

soon be discovered however, that Great Britain had found a way to ignite the

flammable hydrogen gas which gave all zeppelins their lifting power.

|

Airshipmen dwelt heavily upon the subject of being in a burning

zeppelin. To stay on board meant possible survival, but an overwhelming

probability of burning alive. The alternative was to jump, a leap to certain,

but quick, death! One of Peterson's men commented brusquely that there would be

no time for deliberation, that it would all happen much too quickly. Either

way, it was a personal decision which every man dwelt upon to the point of

obsession. When L-31 went down in flames at Potter's Bar, her Captain, Heinrich

Mathy, chose to jump. He was the only zeppelin Captain known to have done so,

and also the only person to have momentarily survived the landing. When local

farmers found Mathy still wrapped in his leather flight jacket, he was face up

in the field near the burning wreckage of L-31. He still lived, but only for a

few minutes, and one wonders whether he had decided on jumping long before, or

whether he leapt to his death in a last moment of fear and decision.

"Our nerves are ruined by mistreatment. If anyone should say that he was not

haunted by visions of burning airships, when he would be a braggart. But nobody

makes this assertion; everyone has the courage to confess his dreams and

thoughts."

Pitt Klein, German Navy Airship

L-31

|

In the summer of 1916, three new types of British

machine gun ammunition which had been under development for years became

available for general use. Two types, named "Pomeroy" and "Brock," after their

inventors, were explosive bullets. The third, called "Buckingham", was a

phosphorus incendiary bullet. Any one of these bullets was only marginally

effective when fired at a zeppelin, but when mixed they formed a lethal

combination. The explosive rounds blew holes in the zeppelin's gas cells,

allowing the hydrogen to escape and mix with oxygen to form an explosive

mixture. The incendiary bullets then ignited the mixed gases. This new mixed

ammunition package was to become Great Britain's wonder weapon against airships

The Autumn Offensive

In the summer of

1916, the new L-30 class ships were delivered to the German Navy and the leader

of airships, Peter Strasser, planned an all out offensive against England. He

was determined to show once and for all that the zeppelin fleet could pour

enough explosives onto targets in England to make a material difference in the

war. There was no doubt as to their morale benefits, the German people loved

the zeppelin fleet and each raid was greeted with the greatest fanfare

throughout Germany. However the British population was seething with anger;

when one airship crashed at sea a civilian British trawler nearby violated the

code of the ocean by not rescuing the airship's crew, standing by to watch them

drown instead.

Three raids were carried out during the first raiding

period in the Autumn and Summer of 1916. On July 31, August 2 and August 8,

Navy airships arrived over Britain during late evening and returned to German

airspace by morning. These raids were uneventful both in the amount of damage

caused to ground targets or airships. As in many previous missions, the

airships continued to overestimate the damage they inflicted, often not

realizing that their bombs were dropping into the sea. However, they also

suffered little or no damage from the still ineffective British air

defenses.

The second raiding period began with another marginally

effective raid on August 24, followed on September 2 by the largest zeppelin

raid of the war. Late on the afternoon of that day, 12 Navy airships; L-11,

L-13, L-14, L-16, L-17, L-21, L-22, L-23, L-24, L-30, L-32 and SL-8 were all

sent into the air. For once, army ships were also to attack the same night.

Four Army airships: LZ-90, LZ-97, LZ-98 and the SL-11 took off from their bases

and headed for England. The sixteen ships carried a total of 32 tons of bombs.

LZ-98, commanded by Ernest Lehmann, future commander of the airship

Hindenburg, approached from the southeast arriving over the Thames River at

Gravesend. Believing that he was over the London dockyards he dropped his bombs

and made off to the northeast, briefly encountering a British aircraft piloted

by Second Lieutenant William Robinson before escaping into the clouds.

| British examine wreckage of SL11 |

|

The LZ-90 crossed the coastline at Frinton and bombed

Haverhill after accidentally losing her sub-cloud car over Manningtree. The

SL-11, commanded by Wilhelm Schramm, arrived over northern London at St.

Albans. As she bombed the northern suburbs the airship was picked up by

searchlights at Finsbury and Victoria Parks. Turning back to the north, the

SL-11 was spotted by Second Lieutenant Robinson, the same pilot who had seen

the LZ-98. Robinson approached and fired two full drums of the new

Brock-Pomeroy ammunition to no effect. As the zeppelin cleared the searchlight

defenses, the British plane made one more pass, firing another full drum into

the airship's side. This time, a bright glow showed inside the ship and within

seconds the fabric burned away as the airship turned into a blazing torch. Her

slow descent to earth at Cuffley was not only seen by all of London, but also

by the Navy zeppelins then making their approach. The L-16, commanded by Erich

Sommerfeld was less than a mile away from SL-11 when she burst into flames, and

she attracted the attention of one of the British pilots chasing SL-11.

Sommerfeld however, sped off to the north escaping the glare before the British

planes could arrive at his position. Of all the airships, Frankenberg in the

L-21 correctly deduced the cause of SL-11's loss. He and his crew miles to the

north could plainly see two aircraft around the army airship, and after she

caught fire one was seen to drop red and green flares (which Robinson did do).

The rest of the airships completed their bombing runs all across eastern

England and safely returned to their bases, having dropped a total of 17 tons

of explosives on British soil. The bombing caused £21,000 worth of

damaged, at the cost of 16 airshipmen dead, and one £93,000 airship

lost.

| Secret funeral for crew of SL11. Public outcry required

military honors to remain discrete. |

|

The third raiding period began when 12 navy airships

headed for Britain late in the afternoon of September 23. The navy crews had

been dismayed by the destruction of SL-11 three weeks previously, but that had

been a wooden army ship. Certainly such a thing could not happen to the veteran

navy captains in their true Zeppelin airships. The new L-30 class ships, led by

Heinrich Mathy in the L-31, worked their way southward and crossed the southern

English coast. This route assured a strong tail-wind and speedy flight past the

most dangerous anti-aircraft areas over London. The other smaller Navy ships;

L-13, L-14, L-16, L-17, L-21, L-22 and L-23 took the direct route into the

Midlands, with only the L-17 causing any casualties at Nottingham. Captain

Alois Böcker in the L-33 was the first to arrive over the capital. He

dropped most of his bomb-load on the East End around Bow and Stratford, with

the airship crew reporting visible fires and explosions with each bomb burst .

However a shell from the defenses over Bromley exploded inside the ship,

causing tremendous physical damage but no fires. She dropped much of her water

ballast which was reported by British ground spotters as a smoke screen, and

made her way eastward losing 800 feet of altitude each minute. After a

dangerous encounter with a British airplane which pumped several drums of

Brock-Pomeroy ammunition into L-33 to no effect, the airship came to earth at

Essex where Böcker and his men jumped to the ground and fired several

flares into her. They were promptly captured as L-33 burned to the ground

having landed mostly intact.

| The bare girders of L-33 after her burning. |

|

Mathy in L-31 arrived an hour after Böcker. At

12:15 A.M. he reported seeing an airship (it was indeed Böcker in L-33) to

the east with large fires burning on the ground in her wake. He followed a

course over Streatham, Brixton and Kennington, dropping most of his bomb load

on the highway running through there. He then made his escape over northern

London at maximum speed. At 1:15 a.m., Mathy saw another airship over what he

thought was Woolwich. It was Captain Werner Peterson in the L-32, which burst

into flames and crashed to earth as Mathy and his crew looked on. Mathy's

report on the event was terse but there was no doubting its traumatic effect on

the crew.

L-32 had come onshore after circling for about an hour.

Peterson's last radio message received was garbled, but it is possible that

L-32 had engine trouble and circled until repairs were made. Up to that point

he and Mathy's ship had been cruising together. When L-32 broke out of the

cloud cover over the Thames River she was spotted almost immediately and pinned

in the searchlight beams of the city's eastern defenses. Peterson may have

realized his danger because L-32 dropped her bombs in rapid succession and

turned toward the sea while attempting to gain altitude. First Lieutenant

Frederick Sowery was in the air that night and nosed his British built BE2c

4112 biplane toward the zeppelin which was so dazzlingly illuminated by the

searchlights. After firing two drums of Brock-Pomeroy ammunition at the

airship, he made a third pass, firing into the side of the zeppelin until he

saw flames on its outer fabric. L-32 quickly caught fire and with her hydrogen

burning off like a blowtorch she dropped slowly to the ground near Snail's Hall

farm, Billericay, killing all on board. After "firing" the zeppelin, Sowery

dropped a red verys light (flare) and then landed at Sutton's farm. Officers of

the Naval Intelligence Division were first on the scene and despite the heat,

they raced through as much of the wreckage as possible (seen at left). They

were rewarded with a copy of the German Navy cipher book, which Peterson had

allowed on board the L-32 against regulations. It will never be known why he

allowed it, if he even knew that it was on board. Its capture was a boon to the

Royal Navy code breakers.

The loss of both L-32 and L-33 had a

serious negative effect on morale. The crash of an army airship was one thing,

but the loss of two veteran navy captains, their crews and their new ships was

altogether different. The next raid, just two nights later was far more

cautious. Captain Ganzel of the L-23 was dismissed after the raid due to his

erratic behavior. His nerves were wrecked and he was transferred to surface

fleet duty. Horst von Buttlar in the L-30 made a cautious approach near the

English coast at Cromer, dropped his bombs in the sea and turned back. Mathy in

L-31 made an audacious attack on Portsmouth, a previously untouched target.

Unfortunately for him, the searchlight defenses were very strong and he

mistakenly dropped his bombs into the harbor instead of on the Navy yard. The

British, who knew from intercepts that it was Mathy were so astonished at not

being accurately bombed that they thought it must have been a reconnaissance

flight; a tribute to their personal opinion of Mathy.

| The wreckage of L-31 as it came to rest at Potter's

bar. |

|

October 1, 1916 was the last night of this bombing

period. Eleven airships headed for England, with only the two L-30's permitted

to attack London. L-30 again reported having bombed targets when in reality she

was not spotted at all over England. Mathy's L-31 approached London from the

Northeast, finally

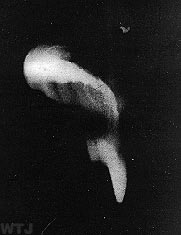

Above: The only

known photograph taken of the L-31 as she fell to the ground at Potter's

Bar |

throttling his engines down in an attempt to float

silently over the listening searchlight operators on the ground. By 12:30 at

least four defense planes were in the air when Mathy fired up his engines and

attracted the searchlight beams. As the guns on the ground opened fire Mathy

dropped his entire bomb-load and turned west. L-31, now several tons lighter,

rocketed skyward and almost escaped. She had cleared the A.A. defenses when

Second Lieutenant W.J. Tempest dove his plane under the airship firing a drum

of Brock-Pomeroy ammunition into the ship's keel. Suddenly, the zeppelin turned

a bright red inside and a burst of flames shot out of her nose. L-31 plummeted

straight to the ground like a freight train, nearly taking Tempest and his

plane with her. As Tempest corkscrewed his plane out of the way the burning

airship passed him and landed at Potters Bar. Local villagers running into the

field found a man lying on his back half-imbedded in the ground. He was alive

and unburned but died soon after. His identity disc was marked: "Kaptlt.

Mathy. L31"

After the morning of October 1, 1916, German

naval airships never again approached Great Britain with their former sense of

impunity. In 1917 and 1918, new airships were built which easily exceeded the

ceilings of British aircraft, but sacrifices in payload and durability were so

great and high altitude bombing accuracy was so poor, that the original goal of

bombing England into submission was quickly lost. The naval airship division

was slowly relegated to the status of reconnaissance arm for the fleet, and as

propaganda weapon for the government. The leader of airships, Peter Strasser

continued to push for his view of a "war ending" zeppelin offensive. He died on

August 5, 1918 while leading the last Zeppelin raid of the war.

recommended reading

Castle,

H.G. Fire Over England. Secker & Warburg, 1982

Manchester

Guardian History of the War. John Heywood LTD. 1916

Robinson, Douglas.

The Zeppelin in Combat. Schiffer Military History, 1994

Scheer,

Reinhard. Germany's High Sea Fleet in the World War. Cassel & Co.

LTD. 1920 |

|